Infrastructure Setup for High Availability

KubernetesGlusterFSCockroachDBtechhigh availabilitySee Introduce K3s, CephFS and MetalLB to My High Available Cluster for updates on this setup.

Cloud is popular these days. But sometimes we just want to host something small, maybe just an open source service for family and friends, or some self-built service that we are still experimenting on. In this case, the cloud can be expensive. We can just throw a few nodes at home and run it at a very low cost. But you don’t want the service down when some nodes fail, at least the service should be available when you upgrade and reboot the nodes because it can happen very frequently. In this article, I will talk about how to build highly available infrastructure so that the service can be alive even when some nodes are down.

What is High Availability?

Availability means a service is alive and can serve traffic. High availability (HA) means when some components of the system are down, the service is still alive. The failed components can be in different layers: it can be a region, a DC, a network, or some nodes. In this article, I’ll only talk about things including and above node level, since region and network are usually out of control for a small infrastructure setup. That means you can host the service on multiple machines, and it should still be alive even when some of the machines are down. This is the most useful case of HA in the case anyway since nodes can be down frequently because of OS or software updates.

Before I start with the real setup, I want to clear some myths about HA first. Maybe you’ve heard of the famous CAP theorem, which says only two of the three properties can be met at the same time: consistency, availability, and partition tolerance. Lots of people misinterpret it as a HA system that will sacrifice consistency during a failure. It is not true: the type of partition that makes you must choose between consistency and availability is very rare. In most well-designed HA systems, you can have both as long as more than half of the nodes are alive (alive also means reachable from clients). And HA doesn’t necessarily mean it prioritizes availability over consistency either: it just means it can handle more failure cases when keeping both consistency and availability. When there is a failure it cannot handle, it can choose to keep consistency and make the service unavailable. This is the type of HA I’m going to introduce in this setup.

So to make it clear, the HA goal in this setup is to make the services still alive without sacrificing consistency when we lose less than half of the nodes (either it’s partitioned from the network or actually dead).

HA Setup

As said before, the HA needs multiple nodes in case of some nodes are down. The setup in this article can tolerate less than half of the node loss. So if you want to have a HA that can handle 1 node loss, the whole system needs at least 3 nodes. There are lots of cheap used machines on the market that have enough power to host many open source services.

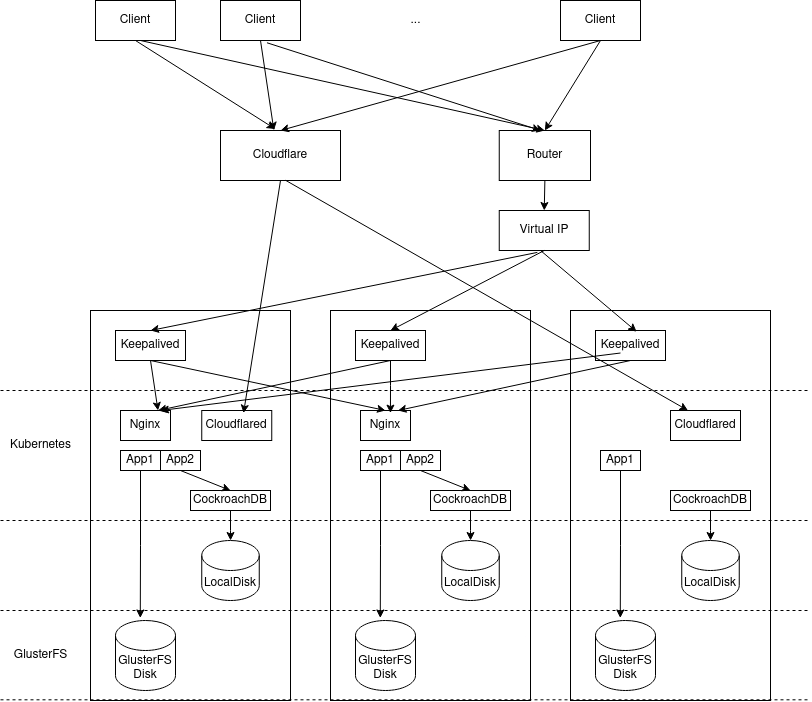

The HA setup has multiple layers and we will use different tools for each of the layers:

- Compute: Kubernetes

- Storage: GlusterFS

- Database: Cockroach DB

- Network Ingress: Cloudflare Tunnel

Here is an overview of the setup:

Update at 2023-11-28: updated the diagram to include Keepalived.

Let’s talk about each of them in detail.

Compute: Kubernetes

Kubernetes is a container orchestration system. Think of it as Docker but across machines. You define what you want to run in the format of YAML or Json, including how much CPU, memory, and storage to use, then Kubernetes will find a node that fits your needs to run your container. It also tries to keep the current system state that meets your definition. For example, if there is a node failure and your service’s container is on it, Kubernetes will try to find another node to start the container so that the state meets the definition. So if the service itself doesn’t have any state between restarts, you get HA for free using Kubernetes.

I must have some warnings about using Kubernetes. It’s a complex project that is used by many big players. It’s not very easy to set up, maintain or upgrade. You need lots of knowledge to make it work. It has so many open issues that your particular needs are most likely not prioritized. While it’s open source so that you can modify the code to meet your use case, and I’ve had good experience contributing code in the early days, the recent experience is not so good anymore: you may need to attend some discussions to push your change instead of async online discussion. That is a lot for a casual contributor. So I end up maintaining a custom branch of Kubernetes with the changes I need locally, which is also a lot for average users.

Even though Kubernetes is heavy, I still think it’s a good tool even for small deployments since it’s already the industry standard. If you want to dedicate the maintenance of the Kubernetes cluster to a third party in the future, you can find lots of providers very easily. And you can just migrate your services to a different cluster without much effort since you’ve already defined the deployment in a language that any Kubernetes cluster can understand.

If you decide Kubernetes is the way to go, Kubernetes can be deployed with Kubeadm. Here is the official document about how to deploy a Kubernetes cluster. Make sure to finish the HA setup so that Kubernetes can survive even if some nodes are down.

Because of the nature of multiple nodes, every time the service restarts, the container can end on a different machine. So if your service needs to store anything on a disk, the data can get lost if you use the local disk of the machine. There are a few solutions for this:

- Just don’t store data on a disk:

- Store it in a database instead. But this is not an option for a service we don’t write and control.

- Send the files to another system. For example, you can send all the logs to something like Elastic Search so that it’s acceptable to lose logs after the container is restarted.

- Use ConfigMaps for configuration files so that you can access them on any machine.

- Bind the service to a specific node so that the container will run on that machine all the time. This needs the service itself to have HA built in so that when that node fails, the containers on the other nodes can still serve traffic. We will see an example of this in Cockroach DB setup.

- The last option is to use a distributed storage system that can be accessed from every machine. We will use GlusterFS for it in this setup.

Storage: GlusterFS

WARNING: Gluster integration for Kubernetes has been removed since Kubernetes 1.26. You can use CephFS instead. Or check Kadulu if you still want to use GlusterFS.

Gluster is a distributed storage system. Once you created a GlusterFS volume, you can mount it to a machine just like NFS. The difference is the volume is backed by multiple machines so if even one of the machines fails, the volume is still usable. Kubernetes could mount a GlusterFS volume for containers as well. Sadly, Kubernetes has removed this support since version 1.26. But I’ve had this setup for a while and is still using an older version of Kubernetes, so I’ll still list GlusterFS as a solution here. The documents are still available for older versions. Here is an example for Kubernetes 1.24. You can select “versions” on the upper right to match your Kubernetes installation. CephFS is another distributed storage system, but it’s less user-friendly than GlusterFS in my opinion since the setup is more complex and it’s harder to mount it locally and explore it like a normal Linux file system. Kadulu seems to be another option if you still want to use GlusterFS, but I’ve never used it and I’m not sure if it’s production ready or not.

See the official install guide for how to install Gluster and set it up. Most of the Linux distros already have the Gluster in the repo so you can install it by the package manager, and configure it based on the official document. Be aware you need to reserve a separate partition just for Gluster.

When creating a Gluster volume for use with Kubernetes, make sure to create it with at least 3 replicas so that you have HA for this volume. One of the replicas can be “arbiter”, which means it’s only used for checking consistency and doesn’t store any actual data. So the data is only duplicated across 2 machines instead of 3 to save some space. Here is an example command to create such a volume:

sudo gluster volume create <volume-name> replica 3 arbiter 1 <host1>:<glusterfs-path> <host2>:<glusterfs-path> <host3>:<glusterfs-path>

Database: CockroachDB

Even though we can make persistence work with distributed storage, it’s better to avoid it if possible because of the setup complexity and performance impact. (This is more of the case of a self-hosted solution, distributed storage from cloud providers is very easy to use, and is also used by the VM so there is no difference in performance). We’ve listed some options above. In this section, we will look at how to create a database for the services to use so that they don’t need to store data on disks.

Here I will use CockroachDB as an example. But this introduction should help you to set up other similar systems like Elastic Search. Cockroach DB is a distributed database that is compatible with PostgreSQL. It’s built with HA in mind, so it has good guarantees and is easy to set up. I’ve checked lots of HA solutions for PostgreSQL and all of them have less guarantee (lots of them have no information about the consistency and availability level they provide, and I found them half-baked with a closer look) while are much harder to set up. I’ve written a blog about Spanner that also talks about Cockroach DB if you are interested in more details. Overall I have a good impression of it: the tech writings are solid, and the support is nice: when I have an issue and report it in the forum, the response is usually very quick and useful even though I’m just a free user.

CockroachDB has an official document about how to install it on Kubernetes. It’s using StatefulSets. Here is one of the configurations it uses. However, I still find there are too many limitations in StatefulSets so I deployed it in my own way:

- Each CockroachDB instance is in its own StatefulSets with only 1 replica.

- Each of the instances is bound to the physical node with PodAffinity. So that each instance will only ever run on a specific host. In this way, we can just use the local disk as the storage because it will never run on a different host.

- Each CockroachDB instance has its own service defined so that they can communicate with each other.

- Copy the parameters from the official configuration and adjust them based on your use case.

With a setup like this, it’s like installing CockroachDB on physical nodes but managed by Kubernetes. You don’t need to worry about distributed storage. When a node fails, a CockroachDB instance will also fail. But since CockroachDB itself has HA enabled, the whole CockroachDB cluster is still alive. Here is an example of the Kubernetes resources in my setup:

# Pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

pod/cockroach01-0 1/1 Running 1 4d11h

pod/cockroach02-0 1/1 Running 5 4d11h

pod/cockroach03-0 1/1 Running 0 4d11h

# StatefulSet

NAME READY AGE

cockroach01 1/1 298d

cockroach02 1/1 298d

cockroach03 1/1 298d

# Service

NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

service/cockroach01-cockroachdb ClusterIP None <none> 26257/TCP,8080/TCP 298d

service/cockroach02-cockroachdb ClusterIP None <none> 26257/TCP,8080/TCP 298d

service/cockroach03-cockroachdb ClusterIP None <none> 26257/TCP,8080/TCP 298d

service/cockroachdb ClusterIP 10.96.70.142 <none> 26257/TCP,8080/TCP 269d

service/cockroachdb-public NodePort 10.108.23.98 <none> 26257:30005/TCP,8080:30006/TCP 269d

You can see there is a separate StatefulSet for each of the CockroachDB instances, and a service for each of them for internal communications (with the name pattern cockroach**-cockroachdb). Service cockroachdb is for the use in Kubernetes cluster, and service cockroachdb-public is used by the service outside of the Kubernetes cluster (can be disabled if not needed) so that you can see the dashboard from your browser.

It may seem to have more Kubernetes definitions to write with such a method. But remember, while Kubernetes accepts YAML or Json format, how to prepare the definition can be flexible: you can use your favorite programming language to construct the definition and pass it to Kubernetes with a client library.

The upgrade of CockroachDB is very easy as well. Make sure to check the official release notes and upgrade guides first, but normally the upgrade is just to patch each of the StatefulSet with a newer version of Docker image, for example:

# run this command for every stateful set

kubectl patch statefulset cockroach01 \

--type='json' \

-p='[{"op": "replace", "path": "/spec/template/spec/containers/0/image", "value":"cockroachdb/cockroach:v22.2.5"}]'

Network Ingress

Once we have everything deployed in the cluster, the last step is to expose our service to the public Internet so that everyone can use it. Here we list two options based on the use case.

Cloudflare Tunnel

Cloudflare Tunnel is basically a reverse proxy that forwards the traffic from the public Internet to your service. There is a daemon called cloudflared running in Kubernetes. Cloudflare will forward the traffic from clients to cloudflared and cloudflared will forward the traffic to the actual service. Check this doc to see how it works with Kubernetes.

The upside of Cloudflare tunnel is that you don’t need to open any port to the public Internet at all. So it’s safer because there is no way to access your service without going to Cloudflare first. Cloudflare also provides some tools to mediate attacks like DDoS.

The downside is it depends on a third-party provider. And it can see all the traffic. It only supports limited protocols. So if you want to avoid Cloudflare seeing your traffic or have a protocol that is not supported, you need a more generic way to do it.

NodePort with Virtual IP and Dynamic DNS

We need to really open a port to the Internet without something like Cloudflare Tunnel. First, we need to open a port on our nodes, this can be done by defining NodePort in Kubernetes’ service.

Once we have the port opened on the nodes, we need to open it to the Internet. How to do it depends on the Internet provider. Usually, you should be able to set up a port mapping from the router to an internal IP for a node. However, to make the setup HA, we shouldn’t map the port just to a single node since that single node can be down, we can set up Keepalived so that there is a virtual IP that always maps to a live node. If you’ve set up HA for Kubernetes with Keepalived and HAProxy, you should be already familiar with how to set it up.

When you open a NodePort, make sure you’ve configured all the protections like authentication and encryption since beyond that it’s public Internet and anyone can access it. You may want to run Nginx or HAProxy in the Kubernetes cluster, use it as a reverse proxy and only expose it to the Internet so that it’s safer and you have more control over the public traffic.

The client also needs a way to find the IP address of your network. Depending on the Internet provider, the IP address can change from time to time. So we need dynamic DNS to bind the changing IP to a fixed DNS. ddclient can do it automatically and supports lots of domain name providers.

After all of this, your service is open to the public Internet and can be accessed by anyone. But if desired, you can still use Cloudflare DNS with proxy enabled, so that the client will send requests to Cloudflare first and you can get protections from Cloudflare. In this case, since the SSL is terminated inside the Kubernetes cluster, Cloudflare will not be able to see the actual payload of the traffic.