Jepsen Test on Patroni: A PostgreSQL High Availability Solution

databasejepsentestdistributed systemconsistencyHANote: code used in this article can be found on the Github repo jepsen-postgres-ha.

I’ve used Cockroach DB for a few of my side projects. I enjoyed it overall. But since it announced license change and require mandatory telemetry collection for free version, I started to look for alternatives. The most natural choice is to just use the plain old PostgreSQL since my data size is not that big and even a less powerful machine can handle it without any problem. One of my important requirements for the database is to have good high availability setup so that I can just shutdown a machine for maintenance from time to time. This series of blog posts will focus on PostgreSQL’s HA solutions instead of why do we need that. Not saying why is not important enough but I’ll save that discussion for another blog post out of this series.

PostgreSQL doesn’t come with native high availability solution. Instead, it has features like replication to support you build your own HA solution. But we all know distributed system is hard to build and error-prone. So I’m planning to test different solutions before I trust my data with them: mainly using Jepsen to test the correctness at first and if it passes the test, benchmark it to make sure it’s usable in real world.

In the first part of this series, I’ll introduce the basic Jepsen test setup. Then use my early test result from Patroni, a very popular PostgreSQL HA solution, as an example. In the test with Patroni, I’m able to:

- Reproduce a known issue that causes violation of read committed isolation. This is related to a fundamental flaw in PostgreSQL’s replication implementation.

- Observe the cluster failed to recover with 1 node lost out of 3 nodes in total.

Ideally I would like to do more tests and deeper digging into it, but I may not have enough free time in the coming 1 or 2 months so I’d like to record some result here and maybe have some updates later.

Jepsen Test Setup

The tool used in the tests is Jepsen. For the ones who are not familiar with it, it’s a tool to test the correctness of distributed systems. I highly recommend anyone interested in distributed systems to read its analyses, which have found bugs in almost every system it has tested, including PostgreSQL 12.3 with single machine setup. On a high level, it runs queries and check if the data is consistent at the end, at the same time it has many built-in failures (nemesis in Jepsen’s term) can be introduced during the query, like node crash, network partition, network slowdown and so on. The analyses of PostgreSQL 12.3 already does an excellent job to explain how Jepsen tests PostgreSQL, so I’ll not repeat it here. I borrowed the append and read workload from that test but with 2 differences on other parts :

- The database is setup in a different way. In the original test, it only tests a single machine PostgreSQL but the bugs are already fixed. So we are going to test a HA setup.

- In the original test, it was able to find bugs without importing any failures. But since that bug has been fixed, we are going to enable different built-in failures like node crash and network slowness to test if the PostgreSQL cluster can still behave correctly or not.

To be more specific, I use Vagrant to create a 3 nodes virtual machine cluster and install Kubernetes (with k3s)on it. The Vagrantfile is here. It’s mostly from a previous project I created to test k3s, as described in the blog post Introduce K3s, CephFS and MetalLB to My High Available Cluster. This setup makes future tests for different HA solutions convenient since most of them supports Kubernetes, so that I can just create yaml files for different systems, while only need to implement Jepsen’s interface once to define database setup, tear down, kill and recover:

- For setup, just use

kubectl create -f <manifest.yaml>. - For tear down, just use

kubectl delete -fto delete the whole thing. - To kill the db, find the root k3s process and

kill -9it along with all its children process. Make sure to also stop the systemd service so it will not be automatically started again. - To recover the db, simply start the k3s service again so that the pods will be scheduled on the node again. It just makes sure the k3s service is started. More health checks are needed if really want to wait for the db to be really recovered but it’s good for now.

Related code is at here.

The code is meant to support any HA setup as long as it can be defined with a Kubernetes manifest. It supports --cluster flag so that can specify which manifest to test. I created a single node PostgreSQL setup and a Patroni setup for now. But in reality, Patroni has some special things that need to be taken care of, like delete PV and endpoints. I’ll clean those things up when my focus is moved to other HA solutions.

For the introduced failures, ideally we should test all the supported failures combined randomly. But the state space is large and need a long time to run. So I just created a specific combination to reproduce a known issue.

A Known Issue of PostgreSQL Replication

When I searched for PostgreSQL HA solutions and whether any of them is tested by Jepsen, I found some comments on Hackernews that says Patroni doesn’t guarantee consistency under some scenarios, which lead me to the Twitter discussion, which states there is a fundamental flaw in PostgreSQL’s replication that makes it really hard to implement HA without data loss.

Here is the problem: usually with synced replication, a transaction should only be committed and visible after the replica db has persisted the transaction. So that if the primary db failed over to replica, there will be no data loss. But in a special scenario, where the query is cancelled after the client sent the commit command, PostgreSQL will consider it as committed even the transaction is not replicated yet. So when a failover happens at this time, this “committed data” will be lost from clients’ point of view. Here is an example:

| Time | Node 1 | Node 2 | C1 | C2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Role: Primary Visible data: k -> [1] |

Role: Replica Visible data: k -> [ 1 ] |

||

| 2 | Role: Primary Visible data: k -> [1] |

T1 start | ||

| 3 | Role: Primary Visible data: k -> [1] |

T1 append 2 to k | ||

| 4 | Role: Primary Visible data: k -> [1] |

T1 commit | ||

| 5 | T1 replication started | |||

| 6 | T1 aborted(conn close? client kill?) | |||

| 7 | T1 replication not finished, but T1 is visible to other clients Role: Primary Visible data: k -> [1,2] |

Role: Replica Visible data: k -> [ 1] |

T2 read k, result = [1,2] | |

| 8 | Node crash | Role: Primary Visible data: k -> [1] |

||

| 9 | T3 read k, result = [1] |

|||

| 10 | T4 append 3 to k | |||

| 11 | Role: Primary Visible data: k -> [1,3] |

|||

| 12 | T5 read k, result = [1, 3] |

In the example above, the value of k is [1] at the beginning. C1 will append monotonically increasing values to k. (It tracks the value locally instead of query k every time). T1 is aborted before it’s replicated. But even so, the primary node still treat this transaction as committed. So when C2 queries with T2, it get results with [1, 2]. Then at time 8, the primary is failed over from node 1 to node 2, so when T3 queries k, it returns [1] instead of [1,2]. This is an obvious data loss in our point of view because we know exactly the order of events. But one can argue it misses linearizable guarantee since technically, T3 can be ordered before T2 or even T1, and it will produce a consistent history, thus violates linearizable but not serializable. However, with T5 that has the result of [1,3], it creates a situation that conflict with T2:

- If T2 is before T5, T5 should has 2 in the result.

- If T5 is before T2, T2 should has 3 in the result.

This is not only a violation of serializability, but also read committed because T2 has read the uncommitted data from the client’s point of view.

Patroni Setup for Testing

Even this is a known issue and is documented, I still try to reproduce it in my test for a few reasons: first, I want to make sure my test is good enough to actually be able to reproduce it. Second, I want to see it happens in real world: the Patroni auto failover makes manually triggering this problem hard because there is only a short time for the commit to be replicated.

In my test, I try to setup Patroni to make it prioritize consistency the most. The config is at here for the Docker’s entrypoint script and here for the config in Kubernetes. The PostgreSQL version is 16 and Patroni version is v4.0.3.

The key configurations are about replication mode. The description of each parameter below is copied from Patroni document about replication modes:

synchronous_modeis set toon: Whensynchronous_modeis turned on Patroni will not promote a standby unless it is certain that the standby contains all transactions that may have returned a successful commit status to client. Turning on synchronous_mode does not guarantee multi node durability of commits under all circumstances. When no suitable standby is available, primary server will still accept writes, but does not guarantee their replication.synchronous_mode_strictis set toon: When it is absolutely necessary to guarantee that each write is stored durably on at least two nodes, enablesynchronous_mode_strictin addition to thesynchronous_mode. This parameter prevents Patroni from switching off the synchronous replication on the primary when no synchronous standby candidates are available.synchronous_node_countis left to default as1: The parametersynchronous_node_countis used by Patroni to manage the number of synchronous standby databases. It is set to 1 by default. It has no effect whensynchronous_modeis set to off. When enabled, Patroni manages the precise number of synchronous standby databases based on parametersynchronous_node_countand adjusts the state in DCS &synchronous_standby_namesin PostgreSQL as members join and leave. If the parameter is set to a value higher than the number of eligible nodes it will be automatically reduced by Patroni.

In PostgreSQL:

synchronous_commit: "on"

synchronous_standby_names: "*"

max_connections: 500

As stated in the Patroni doc, even with this setup it still has the known issue described above:

Note: Because of the way synchronous replication is implemented in PostgreSQL it is still possible to lose transactions even when using synchronous_mode_strict. If the PostgreSQL backend is cancelled while waiting to acknowledge replication (as a result of packet cancellation due to client timeout or backend failure) transaction changes become visible for other backends. Such changes are not yet replicated and may be lost in case of standby promotion.

This is the thing I want to reproduce.

Reproduce Read Committed Violation

The reproduction of this failure is harder than I thought, even I knew exactly the requirement to trigger it at the beginning. There are a few factors contributed to this:

First, if the client doesn’t abort the connection itself, it’s hard to reproduce this scenario: The client not aborting the connection means it’s aborted by the primary node, which needs to introduce some failures to the primary node and that most likely makes it to failover immediately before the failure scenario is triggered. Jepsen’s built-in failures/nemesis are mostly on the server side. While not familiar with Clojure, it took me some time to figure out how to abort the connection just after sending the commit command. The code is at here:

(if (and break-conn (not read-only?))

(let [result-chan (chan)

close-chan (chan)

]

(go (>! result-chan (try (run) (catch Throwable e e))))

(go (<! (timeout 120))

(try (c/close! conn) (catch Throwable e e))

(>! close-chan true))

(<!! close-chan)

(let [result (<!! result-chan)]

(if (instance? Throwable result)

(throw result)

result

)))

(run))))

break-conn is a boolean that produced from a random number. If it’s not a read only transaction, the client will close the connection after a timeout of 120ms. As I will talk about later, I introduced the network slowdown to make the round trip about 100ms in average, so a complete replicated transaction should take 100ms (client to primary) + 100ms (primary to replica) = 200ms. So 120ms will hopefully makes the connection abort after the commit command is sent to the primary but before the transaction is replicated. This is definitely not perfect, but it’s the best I can do for now.

Second, the nemesis package I copied from the original test is not very suitable to reproduce this issue: it randomly introduce different failures (passed in by cli flags) by a predefined average interval. So it needs some luck to get the scenario that triggers this failure: a combination of slow network + primary failure. So after I studied the failure scenario again, I changed the nemesis suite to create slow network all the time, and create a 90 seconds cycle for primary failure (30 seconds healthy state + 60 seconds node killed).

Third, the default work load will create multiple keys and run multiple ops in a single transaction. Which makes it harder to trigger the exact scenario (the transaction network round trip time will be different depends on the number of ops so 120ms is less likely to close connection after commit). After thinking more about the requirement to trigger the failure, I tuned the parameters to operate on a single key most of the time and only have a single operation per transaction.

The other factors are mostly about my setup with VM + Kubernetes. For example, I need to figure out ways to do things like crash the node (k3s root process + children process). I also need to adjust the network interface name in network related failures since the VM created eth1 instead of eth0 hard coded in Jepsen.

At last, you need a little bit luck: the failures is hard to trigger so my test doesn’t reproduce it every time. Just before I decided to give up, it showed the error. The command to reproduce it is in the readme:

for i in `seq 1 10` ; do

lein run test --nodes-file ./nodes --username vagrant -w append --concurrency 10 --isolation serializable --nemesis packet,kill --time-limit 1800 -r 100 --nemesis-interval 60 --break-conn-percent 0.8 --cluster patroni --key-count 1 --max-txn-length 1 --max-writes-per-key 24000 --nemesis-suite slow-net-kill

sleep 30

done

Some key params:

--time-limit 1800: run the test for 1800 seconds.-r 100: send 100 queries per second.--break-conn-percent 0.8: 80% of the append transactions will be closed after 120ms.--key-count 1 --max-txn-length 1 --max-writes-per-key 24000: operate on a single key until the operations exceed 24000 times.

As stated above, the test slows down the network the whole time to an average of 100ms round trip. At the same time, it does this loop: wait 30 seconds. Kill the primary node by killing the k3s process and all its children processes. Wait 60 seconds. Start k3s service again.

At last, the outer for loop runs the command 10 times so it has a higher possibility to trigger the failure.

As for why to run the test 10 times instead of a single round of 300 minutes, it’s related to another problem I found during the test which will be discussed in the later sections.

An example of the failure from a recent run:

:workload {:valid? false,

:anomaly-types (:incompatible-order),

:anomalies {:incompatible-order ({:key 0,

:values [[4

6

8

9

// ... omitted lines of numbers

7164

7171

7176

7181]

[4

6

8

9

// ... omitted lines of numbers, the same as before

7164

7171

7176

8433]]})},

:not #{:read-committed},

:also-not #{:causal-cerone

:consistent-view

:cursor-stability

:forward-consistent-view

:monotonic-atomic-view

:monotonic-snapshot-read

:monotonic-view

:parallel-snapshot-isolation

:prefix

:read-atomic

:repeatable-read

:serializable

:snapshot-isolation

:strong-read-committed

:strong-serializable

:strong-session-read-committed

:strong-session-serializable

:strong-session-snapshot-isolation

:strong-snapshot-isolation

:update-atomic

:update-serializable}},

:valid? false}

If you check the last 2 numbers for the 2 transactions listed above: one transaction reads [..., 7176, 7181] and another one reads [...., 7176, 8433]. It reproduced the exact problem we discussed in the last section.

One thing to notice is that even though the behavior of this failure is the same as we discussed in the last section, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the same root cause. I say that because this failure is so hard to trigger and I’m not sure yet what exactly triggered it. This is another thing I want to dig deeper into but may not have the time in the near future.

Failed to Recover the Cluster When Only 1 Out of 3 Nodes is Lost

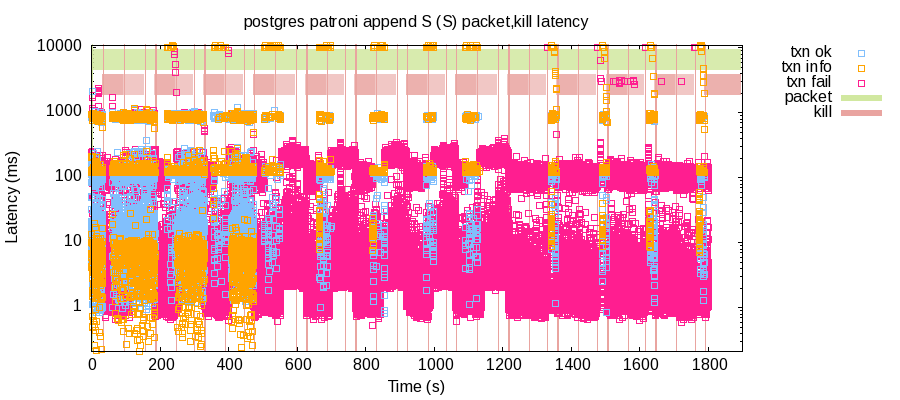

Jepsen generates some graphs after the test. So you can see how the database behaves during the test. The following graph is one of them. It’s the latency of each transaction and the time range of imported nemesis:

The green area at the top means the time that network is slowed down, which is basically during the whole test time in our case. The red part is when the primary node is killed by our test: the lighter red part means the killed node starts to recover by the test until it reaches the white part which means it has been recovered (we mark it as recovered as soon as k3s server is recovered, so it’s not that accurate).

Each square/point represents a transaction. You can see even without primary node being killed, there are still some failed transactions and that’s totally normal in our test: it has errors like conflicted transactions and max connections reached etc. The thing more relevant is whether there are successful transactions, which the blue square/point represents.

We can see during the first few rounds when the primary get killed, the cluster can recover with 2 of 3 nodes available (the red range). However, as time passed, it can only recover when all the nodes are available (the white range). At the end of the test, there are 2 of 3 nodes available (sometimes there are all 3 nodes available because the recovery time are not always the same so the end state of the test can also be different). Just out of curiosity, I wanted to see how much time Patroni needs to recover in such state, so I left it without making the failed node available and waited. However, after 20 minutes, the cluster is still not recovered.

This means the cluster failed to recover even if you only lose a minority of the nodes. After I asked in the Github issue, I got confirmed that Patroni cannot be auto healed from such state. Apparently this is kind of a known behaviour but came as a surprise to me. To be fair, the behaviour of the parameters are documented but it’s hard to realize the implication. Again quoted from the description before:

synchronous_node_count: If the parameter is set to a value higher than the number of eligible nodes it will be automatically reduced by Patroni.

It’s not clear what “eligible nodes” means but it seems it means available nodes instead of all nodes in the cluster.

synchronous_mode_strict: When it is absolutely necessary to guarantee that each write is stored durably on at least two nodes …

So it’s two nodes instead of a majority of the nodes: if you have a 5 nodes cluster and you happen to lose the 2 nodes with the most up to date data, it’s not possible to recover the data anymore.

Checking the doc again, it seems quorum commit mode is something can help here. But test with synchronous_mode=quorum still got the same result. And from the doc:

On each iteration of HA loop, Patroni re-evaluates synchronous standby choices and quorum, based on node availability and requested cluster configuration. In PostgreSQL versions above 9.6 all eligible nodes are added as synchronous standbys as soon as their replication catches up to leader.

From the test, it seems the availability of nodes also affects the quorum.

Back to the question about why need to run the tests multiple times instead of running a single longer test: because the cluster doesn’t recover by itself during a node loss after a few kill loop, which means more time is needed for the healing between node kills and makes the test less efficient. Also, when wait enough time between node kills, I was not able to reproduce the read committed violation anymore. That’s another reason that I’m suspicious if it is really caused by early connection close or not.

Ways to Improve?

With a quorum based system, there is \(V_w\) means the min nodes to write for a write transaction. There is \(V_r\) means the min nodes to read for a read transaction. In order to maintain serializability, \(V_w + V_r > V\) needs to be true where \(V\) is the number of all nodes, so that \(V_w\) and \(V_r\) has at least 1 node overlapped. That means when a client reads data from \(V_r\) nodes, at least 1 node has the latest data. In our case, for the normal read transactions, \(V_r\) doesn’t matter since it only reads from the primary so it’s guaranteed to have the latest data. But when doing a failover, we need to make sure having \(V_r\) nodes available because primary is lost and we need to determine which node has the latest data.

In the case of Patroni, with synchronous_node_count can be auto reduced and synchronous_mode_strict only guarantees data writes to at least 2 nodes, \(V_w\) is essentially set to 2 which means in order to maintain consistency, \(V_r > V - V_w = V - 2\) needs to be true, which means it only tolerates 1 node lost no matter the cluster size. But even with only 1 node lost in our test above, Patroni didn’t implemented auto failover.

So to make it better tolerate node loss, there should be an option similar to synchronous_node_count but actually enforce the minimal synced replication count instead of reduce it based on node availability. And if the available nodes meets the requirement of \(V_r\), do the auto failover by comparing the largest LSN on each node.

Update: it’s actually a tricker problem to resolve if not changing PostgreSQL internals. See the section “Quorum” in my newer article What Happens If Raft Algorithm Is Not Fully Implemented.

Minor Issue: Wrong Role Label for Kubernetes Pod

At last there is a minor issue but also the first issue I found during the test: in the Patroni doc, it uses the command kubectl get pods -L role -o wide to show the role of each Patroni pod. However, it is inaccurate as confirmed in the Github issue. It’s not a big deal but something to be aware of when operating Patroni. I think theoretically it may be able to be fixed by letting the primary pod set the k8s labels for all the other pods.

What’s Next?

Ideally, I still want to dig deeper into Patroni’s test since it’s a very popular PostgreSQL HA solution. The test above is only a carefully create scenario based on a known issue. Running larger scale tests with more combined failure scenarios may be able to find more failure modes. However, because of the fundamental PostgreSQL replication flaw described above and the effort needed to run the large scale tests, I may want to setup and test another solution first.

The solution is what I had in mind even before I started Patroni’s Jepsen test, which is to set up replication with DRBD: instead of using PostgreSQL’s replication, DRBD replicates the whole disk instead. With modern hardware, the performance with replication overhead should be acceptable but it remains to be tested, along with the correctness of it.